My students have written an ebook!

You can read it for free here.

From an ELT perspective, this ebook is the result of a semester-long CLIL class, with project-based learning and a real and motivating outcome! If you want to find out how we did it, this post is for you!

Context

Our class was on British cultural studies, aimed at master’s level students of English Studies. This class aims to promote language learning and learning about content, in this case a particular British cultural topic. Usually, students are expected to do one oral presentation and one piece of written work as the assessment for this class. Only the other class members see the presentations, and the individual teacher is the only one who reads the essays, in order to grade them. I’d say this is a pretty standard set up.

Background

Last summer, a colleague and I revamped our British cultural studies classes to move towards project-based learning. In 2016, our students hosted an exhibition open to staff and students a the University, which you can read about here. It was pretty successful, though the students involved found it a shame that all their hard work was only seen by a limited audience. Of course, the audience was a lot less limited than usual, but that’s what they said anyway…!

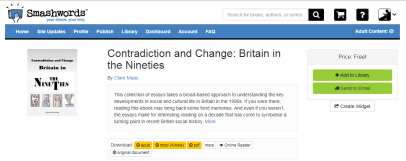

And so I came up with the idea of producing an ebook this year, which could then be made available publicly. I had seen other organisations use smashwords, and read about how easy it could be to publish a book through that site, so that’s what I thought we should do. I chose the umbrella topic of Britain in the Nineties for our focus, and 23 students signed up. I provided an outline for the class, which included a general module description, assessment requirements for the module, a provisional schedule for the ebook (to be sent to publish in the last week of semester!), and a selected bibliography of recommended reading on the topic.

Our semester is 14 weeks long, with one 90-minute lesson of this class each week. So how did we manage to produce an ebook in this time?

Weeks 1-3

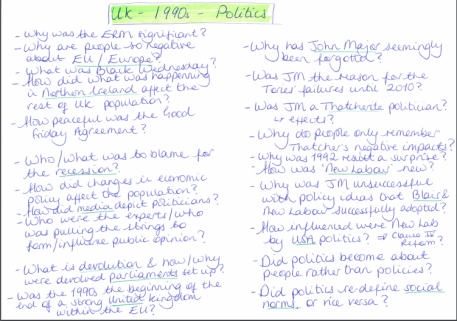

In the first three lessons, I provided a video documentary, an academic article and a film for students to watch/read as a broad introduction to the topic. In lessons, we collected the main themes from this input (key words here: politics, music, social change), and discussed how they were interlinked. Each week, a different student was responsible for taking notes on our discussions and sharing these on our VLP for future reference. In week three, we rephrased our notes into potential research questions on key topic areas.

At the end of each lesson, we spent some time talking about the ebook in general. As the semester progressed, the time we spent on this increased and resembled business-like meetings.

Week 4

By this point, students had chosen topics / research questions to write about and discussed their choices in plenary to ensure that the ebook would present a wide-spread selection of topics on Britain in the Nineties. The students decided (with my guidance!) to write chapters for the ebook in pairs, and that each chapter should be around 2000 words, to fulfil the written assessment criteria of the class. Writing in pairs meant that they automatically had someone to peer review their work. To fulfil the oral assessment criteria, I required each writing team to hold a ‘work in progress’ presentation on the specific topic of their chapter. I had wanted to include these presentations to make sure I could tick the ‘oral assessment’ box, and because having to present on what they were writing would hopefully mean they got on with their research and writing sooner rather than later!

Weeks 5 & 7

The lessons in these two weeks were dedicated to writing workshops and peer review. We started both lessons by discussing what makes for good peer review, and I gave them some strategies for using colours for comments on different aspects of a text, as well as tables they could use to structure their feedback comments. These tables are available here. Regarding language, these are post-grad students at C1 level, so they’re in a pretty good position to help each other with language accuracy. I told them to underline in pencil anything that sounded odd or wrong to them, whether they were sure or not. If they were sure, they could pencil in a suggestion to improve the sentence/phrase, and if not then the underlining could later serve the authors as a note to check their language at that point.

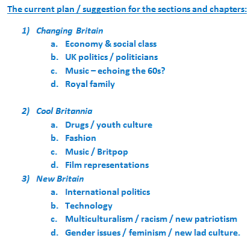

In week 5, we looked at different genres of essay (cause/effect, compare/contrast, argument, etc), and how to formulate effective thesis statements for each of them. This focussed practice was followed by peer review on the introductions students had drafted so far. By this point, the students had decided that their chapters could be grouped thematically into sections within the ebook, and so did peer review on the work of the students whose chapters were going to be in the same section as their own.

In week 7, we reviewed summaries and conclusions, and also hedging language. Again, this was followed by peer review in their ‘section’ groupings, this time on students’ closing paragraphs.

Weeks 6 – 11

Almost half way through the semester, all writing teams were working on their chapters. In the lessons, we had a couple of ‘work in progress’ presentations each week. Further to my expectations, the presentations did an excellent job at promoting discussion, and particularly prompted students to find connections between their specific topics – so much so, that they decided to use hyperlinks within the ebook to show the readers these connections. Some students also used their presentations to ask for advice with specific problems they had encountered while researching/writing (e.g. lack of resources, overlaps with other chapters), and these were discussed in plenary to help each writing team as best we could. The discussions after the presentations were used to make any decisions that affected the whole book, for example which citation style we should use or whether to include images.

Week 12

In week 12, all writing teams submitted their texts to me. This was mainly because I needed to give them a grade for their work, but I also took the opportunity to give detailed feedback on their text and the content so they could edit it before it was published. I was also able to give some pointers on potential links to other chapters, since I had read them all. I felt much more like an editor, I have to say, than a teacher!

In the lesson, we had a discussion about pricing our ebook and marketing it. To avoid tax issues, we decided to make the ebook available for free. One student suggested asking for donations to charity instead of charging people to buy the book.

This idea was energetically approved, and students set about looking into charities we could support. In the end, SHINE education charity won the vote (organised by the students themselves!) I dutifully set up a page for us on justgiving.com: If you’d like to donate, it can be found here.

At this point, we also discussed a cover for the book. One student suggested writing ‘the Nineties’ in the Beatles’ style, to emphasise the links to the 1960s that some chapters mentioned. We also thought about including pencil sketches of some of the key people mentioned in the book, but were unable to source any that all students approved of. Instead, students used the advanced settings on the google image search to find images that were copyright free. A small group of students volunteered to finalise the cover design, and I have to say, I think they did a great job!

Week 13

During the lesson in this week, the ebook really came together. Some of the students were receiving more credit points than others for the class, based on their degree programme, and so it was decided that those students should be in charge of formatting the text according to smashwords’ guidelines, and also for collating an annotated bibliography. I organised a document on google docs, where all students noted some bullet points appraising one source they had used for their chapter, and the few who were getting extra points wrote this up and formatted it into a bibliography.

Formatting the text for publication on smashwords.com was apparently not too difficult, as the smashwords’ guidelines explain everything step-by-step, and you do not need to be a computer whizz to follow their explanations!

Week 14 and beyond

This week was the deadline I had set for sending the ebook for publication. After the formatting team had finished, I read through the ebook as a full document for the first time! I corrected any langauge errors that hadn’t been caught previously, and wrote the introduction for the book. This took me about 2 evenings.

Then I set myself up a (free) account at smashwords.com and uploaded the ebook text and cover design. Luckily, the students had done a great job following the formatting rules, and the book was immediately accepted for the premium catalogue! (*very proud*)

Another small group of students volunteered to draw up some posters for advertising, and to share these with all class members so we could publicise the ebook on social media, on the Department’s webpage, and in the University’s newsletter.

Et voila! We had successfully published our ebook in just 14 weeks!

Evaluation

I’m so glad that I ran this project with my students! It honestly did not take more of my time than teaching the class as ‘usual’ – though usually the marking falls after the end of term, and it was quite pressured getting it done so we could publish in the last week! In future, I might move the publication date to later after the end of semester to ease some of the stress, though I do worry that students’ might lose momentum once we’re not meeting each week.

The students involved were very motivated by the idea that the general public would be able to read their work! I really felt that they made an extra effort to write the best texts they could (rather than perhaps just aiming to pass the class). This project was something entirely new for them, and they were pleased about their involvement for many reasons, ranging from being able to put it on their CV, to seeing themselves as ‘real’ writers. They have even nominated me for a teaching prize for doing this project with them!

Sadly, one student plagiarised. Knowingly. She said that she was so worried her writing wouldn’t be good enough, so she ‘borrowed’ large chunks of texts from an MA dissertation which is available online. Her writing partner didn’t catch it, and was very upset that their chapter would (discreetly!) not be included in the ebook. He was very apologetic to me; and probably also quite angry at her. If the reason she gave was true, it obviously rings alarm bells that I was expecting too much from the students or didn’t support them enough. I will aim to remedy this in future. It could, of course, just have been an excuse.

Also, some other students reported feeling that this project demanded more work from them than they would normally have to put into a class where the grade doesn’t count. Maybe this is because writing in a pair can take more time and negotiation, or maybe they also felt stressed by having to write their text during term time, rather than in the semester break when they would normally do their written assessments. Overall, though, the complaints were limited and often seemed to be clearly outweighed by the pride and enjoyment of being involved in such a great project!

I’m really pleased with how this project panned out, and would recommend other teachers give it a go! I’m very happy to answer any questions in the comments below, and for now, I wish you inspiration and happy ebook-project-planning! 🙂

The acronym CLIL stands for “Content and language integrated learning” and was coined by David Marsh to denote an approach to language teaching with a dual aim, namely learning a foreign langauge and simultaneously learning something new about a subject, new content.

The acronym CLIL stands for “Content and language integrated learning” and was coined by David Marsh to denote an approach to language teaching with a dual aim, namely learning a foreign langauge and simultaneously learning something new about a subject, new content.

Focussing on the policy areas they have chosen and the supporting evidence they have analysed, and employing the language features they noted down from the party political broadcast, the party groups then create short speeches / party political broadcasts (max. 5 mins) to present and promote their policy ideas to the class group (=target voters). To ensure that all students speak, each one can present one policy idea. Students can also create one poster or PPT slide to advertise their party, main policies, and candidate.

Focussing on the policy areas they have chosen and the supporting evidence they have analysed, and employing the language features they noted down from the party political broadcast, the party groups then create short speeches / party political broadcasts (max. 5 mins) to present and promote their policy ideas to the class group (=target voters). To ensure that all students speak, each one can present one policy idea. Students can also create one poster or PPT slide to advertise their party, main policies, and candidate. Once all of the speeches have been heard, the room can be re-arranged to make polling booths, where students will be able to cast their vote anonymously. The teacher hands out the ballot papers, and provides a ballot box for the students to cast their vote in.

Once all of the speeches have been heard, the room can be re-arranged to make polling booths, where students will be able to cast their vote anonymously. The teacher hands out the ballot papers, and provides a ballot box for the students to cast their vote in.